Up until about 1960, road graders from all manufacturers used powered mechanical drives from the cabin to enable the operator to make adjustments to the grading implements on the machine, whilst on the move. After that time, hydraulic actuators began to be fitted and graders became simpler and easier to drive, but less interesting to model in Meccano.

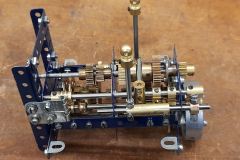

The model described here replicates a late 1950s era mechanical grader in 1/8 scale, making it almost 3 feet long, and weighing 12.5kgs. The central component is the six-way gearbox, positioned in the cab in front of the operator. This provides Forward-Neutral-Reverse independent motion outputs, powering drive shafts running forward along the machine to enable the various blade and scarifier adjustments to be made. Due to the limitations of the size of Meccano gears, the gearbox could not be modelled to scale so it is overly large in the cabin.

The six motions are: Blade Height (separate left and right side); Blade Angle of Attack (via a turntable); Blade Side-shift (using a curved rack gear); Scarifier Depth; and Front Wheel Lean (to counteract side drift when grading).

Extensive use is made of universal joints to get the drives to remote parts of the machine. In the model, small neat universals are used, purchased over the internet for reasonable prices. In total, there are 13 universals on the model, eight of them crowded into the small space in front of the six-way gearbox.

The rear wheel drive transmission is from a 12Vdc motor hidden in the outline of a diesel engine, through an in-line planetary clutch and into a six speed forward, two speed reverse gearbox, located beneath the cab. This is really a three speed and reverse gearbox with an attached two speed high and low range gearbox. Forward ratios are 6:1, 4.5:1, 3:1, 2:1, 1.5:1 and 1:1. Reverse ratios are 7.89:1 and 2.63:1. An H-pattern gearchange operates the main gearbox. Spring-loaded detents are fitted to both levers.

A rigidly mounted differential sits beneath the engine, with its half shafts emerging on either side to enter the middle of the chain boxes. From the ends of the half shafts, two chains and sprockets take the motion to the wheel axles at the ends of each chain box. Commercial ¼” pitch roller chain and sprockets obtained from the internet, create a heavy duty final drive with 20:9 reduction. Interestingly, the ¼” chain pitch is exactly 1/8 of the 2” chain used in the prototype, keeping the scale correct.

The 12V motor’s speed is controlled by a bespoke Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) speed controller. A potentiometer with attached small lever sits conveniently at the right-hand end of the six-way gearbox, in a similar position to the prototype. Brakes are not fitted to the model but a simulated handbrake drum is mounted underneath at the front end of the transmission.

The weight of the model at the rear is too great for standard Meccano rods to bear, so a floating axle arrangement was devised between the chassis and the chain boxes. Special 5/16” flanged pivot bearings were made to carry the load, and they are hollow, which allows the drive shafts to pass through freely to the sprockets. This arrangement is a true floating axle arrangement similar to the prototype.

Suitable tyres are not available in the Meccano parts range, so I was lucky to come across a source of very realistic-looking ashtray tyres which nicely enhance the model’s appearance. The tyres are mounted on hubs built up using Ovaltine tin lids.

Road graders are capable of tilting their blade outwards and upwards on either side, to perform Bank Cutting, which is grading the sloping sides of road cuttings. The model can replicate this as seen in the picture. Slides on the back of the blade enable it to be manually pushed out to either side. Bespoke turnbuckles were made for the model and fitted in place of the fixed-length linkages which control the heights of the ends of the blade. By shortening the length of one of the turnbuckles and lengthening the other, and tilting the turntable, the blade can be made to move to the bank cutting position.

The special turnbuckles were made from ¼” brass rod, drilled and tapped at each end for M4 threads; right hand thread at one end and left hand at the other. Suitable partly threaded rods, again M4 right hand thread and M4 left hand, were also made to complete each assembly. The maximum achievable angle of the model’s blade from the horizontal is 65 degrees.

Considerable work went into modelling the front axle which has three functions. It has to pivot in the centre for the simple beam suspension; it has to have kingpins at its outer ends to allow the front wheels to steer; and its outer ends also have horizontal pivots for the front wheels to be leaned either side to counteract side forces when grading. The resultant axle knuckles’ movements are three dimensional and complex.

The model was constructed to be easily dismantled in modules. The cabin requires only two screws and the steering wheel to be taken out, for its removal. The engine cover easily lifts off because it is held in place by four pins (actually the ends of slightly longer Meccano screws poking through chassis holes). The differential and chain boxes assembly can be removed by undoing four screws. The engine and gearbox module can be removed by undoing four screws. The six-way gearbox is held in place by two side rods, but for removal, four universal joints and two long shafts have to be disconnected first.

This Grader is actually the most complicated model I have ever built and it took about two years to complete in my spare time. The difficulties arose from trying to maintain scale reproduction of the various mechanical drives while fitting them realistically into and onto the skeleton chassis.

I was inspired to build a model grader as a young boy when I read about a similar model in the July 1960 edition of the Meccano Magazine. It was built by Alan Wenbourne who was then an engineering apprentice working for a company in England which made earthmoving equipment. At the age of 11 in 1960, I wondered if I would ever be able to make such a large and complex model. Finally I have, but it took me 60 years to realise my ambition!